Bio

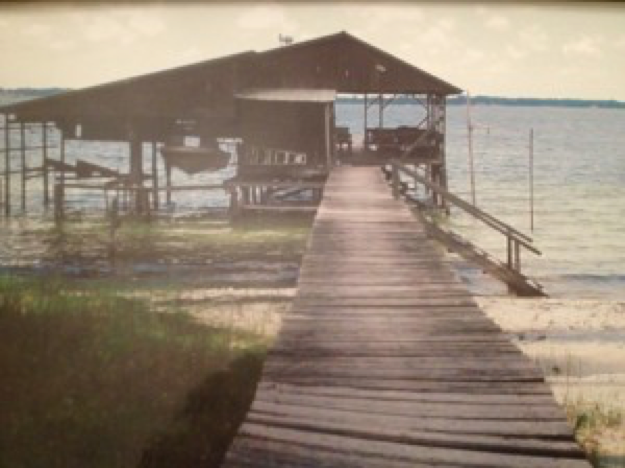

I grew up in the South, born into a family of outrageous storytellers–the kind of storytellers who would sit on the dock by the lake in the evening and claim that everything they say is THE absolute truth, like, stack-of-Bibles true. The more outlandish the story, the more it likely it was to be true. Or so they said.

I grew up in the South, born into a family of outrageous storytellers–the kind of storytellers who would sit on the dock by the lake in the evening and claim that everything they say is THE absolute truth, like, stack-of-Bibles true. The more outlandish the story, the more it likely it was to be true. Or so they said.

You want examples? Okay. There was the story of my great great aunt who shot her husband dead, thinking he was a burglar; the alligator that almost ate Uncle Jake while he was waterskiing; the gay cousin who took his aunt to the prom, disguised in a bouffant French wig. (The aunt, not the cousin.) And then there was my mama, a blond-haired siren who, when I was seven, drove a married man so insane that he actually stole an Air Force plane one day and buzzed our house. (I think there might have been a court-martial ending to that story.)

And in between all these stories of crazy, over-the-top events, there was the hum of just daily, routine crazy: shotgun weddings, drunken funerals, stories of people’s affairs and love lives, their job losses, the things that made them laugh, the way they’d drink Jack Daniels and get drunk and foretell the future. A great aunt who was in a lightning storm and had her hat fused to her head. There were ghosts and miracles and dead people coming back to life and rattlesnakes jumping out of drain pipes and coming up inside toilets in the middle of the night. You know, everyday stuff.

How could I turn into anything else but a writer? My various careers as a substitute English teacher, department store clerk, medical records typist, waitress, cat-sitter, wedding invitation company receptionist, nanny, daycare worker, electrocardiogram technician, and Taco Bell taco-maker were only bearable if I could think up stories as I worked. In fact, the best job I ever had was a part-time gig typing up case notes for a psychiatrist. Everything the man dictated bloomed as a possible novel in my head.

Still, I was born with an appreciation for food and shelter, and it didn’t take me long to realize that coupling a minor in journalism to my English degree might be a wise move, even though I had never for one moment felt that passion for news that my newspaper colleagues claimed beat in their breasts. I am famous for raising my hand in Journalism 101 and saying, incredulously, to the professor, “You don’t mean to tell me that every single detail in the story has to be true? Every one? Really?”

Still, I was born with an appreciation for food and shelter, and it didn’t take me long to realize that coupling a minor in journalism to my English degree might be a wise move, even though I had never for one moment felt that passion for news that my newspaper colleagues claimed beat in their breasts. I am famous for raising my hand in Journalism 101 and saying, incredulously, to the professor, “You don’t mean to tell me that every single detail in the story has to be true? Every one? Really?”

Learning to write only truth was a tough discipline, and as soon as I could, I left the world of house fires and political scandals and planning and zoning commission meetings and escaped into a world of column-writing, and then, magazine writing. (Way, way better to be assigned to think of 99 ways of getting him to declare his love, rather than be stuck writing about the bond proposal for the sewer lines.) But all along the way, in between deadlines and raising three children and driving them to their sports games and tucking them in at night and doing the laundry and telling them stories, I was really writing a novel about marriage and relationships and the way regret has of just showing up alongside your life, just when you think things are as rosy as they could be.

Today I live in Connecticut, and spend part of every day bent over my laptop, writing and writing and writing, looking out at the willow tree and the rosebush and the rhododendron that has a nice nest of cardinals—either that, or the snowy, silent woods, the deep black of the branches iced with clumps of snow.

The lakehouse is gone now, and so are most of my more outrageous story-telling relatives, although there are a couple still out there spinning their yarns. And I am far from where I began, living a life that has turned out to be tamer and yet more satisfying than anything I had any right to expect. (No rattlesnakes in the toilet, for one thing!) But I know that I was nourished by those stories—they are part of who I am—and I can still remember my mother’s cheeks burning red, her eyes frightened and dancing, as the wings of that Air Force jet dipped and did a little salute to her and to love and to unrequited passion…and probably to hope that she would leave my father and run away. I was scared and exhilarated both, seeing that my mother had this power and this whole other life besides the one I spent with her.

The lakehouse is gone now, and so are most of my more outrageous story-telling relatives, although there are a couple still out there spinning their yarns. And I am far from where I began, living a life that has turned out to be tamer and yet more satisfying than anything I had any right to expect. (No rattlesnakes in the toilet, for one thing!) But I know that I was nourished by those stories—they are part of who I am—and I can still remember my mother’s cheeks burning red, her eyes frightened and dancing, as the wings of that Air Force jet dipped and did a little salute to her and to love and to unrequited passion…and probably to hope that she would leave my father and run away. I was scared and exhilarated both, seeing that my mother had this power and this whole other life besides the one I spent with her.

Despite all this, I’m afraid I’ve turned out pretty normal: married, children, grandchildren, dishes in the sink, deadlines, laundry, sleep deprivation, toothpaste cap lost, cashmere sweater in the dryer by accident. The full catastrophe, as Jack Kornfeld put it.

But the great thing about being a writer is that I get to have lots of different lives, not just this one that often feels so short and filled with choices that I already made. Sometimes other people seem to come and set up housekeeping in my head, and they tell me everything about themselves—they unpack for me all their intriguing secrets and fears and fantasies, and I sit back and close my eyes and let them talk and talk and talk while I let it all soak into my head. I argue with them, and they argue back, and a story starts to form from our talks, and for a while it feels as though I am that person and also me at the same time, in a very strange way. And it’s then that I remember the wide Florida sky and the heavy, humid air and the nighttime storytelling, the voices on the dock of the lakehouse, and I know that we never ever know what’s going to happen.

I just get to write it all down, bring it to something that’s similar to life. And that’s the most fun of all.